It’s common to hear stories from people about how they started a yeast starter but forgot about it and had to throw it away.

Another common comment is about how finicky people assume starters are.

Yes, there are some things to keep in mind and understand about yeast when keeping a starter. However it doesn’t have to difficult to keep a starter. And yeast is much healthier than most people assume. You have to remember that yeast is found in the air around us. It lives on our skin and is an invisible friend. It was created to survive in the same world that we live in.

One of the common misconceptions that I find people perpetuates in starting and feeding yeast is that you have to have a wet starter. Ever since I posted about keeping a drier starter, more and more people are talking about how they now keep a dry starter. And before I posted on my blog, I talked about this in community pages. In one thread a microbiologist agreed that it made more sense to keep a drier starter of yeast.

The benefit of keeping a drier yeast is that you do not have hooch (a liquid layer on top of your starter) by week’s end.

I firmly believe that hooch is an indication that your environment for your starter is out of balance. Excess water created a home for bacteria and mold to grow and ultimately lead to a situation where you have to throw your starter out. Once mold forms, there’s nothing you can do to resuscitate your yeast. That is the one kiss of death to starter.

And mold loves water.

If you keep your water levels in check, you don’t have to do anything else to prevent mold.

How can I state that with surety?

Let’s just say that the Christmas season was so busy that I forgot about my yeast for an entire month! Perhaps over a month… I last used my starter for Thanksgiving and forgot about it until after the New Year.

My Neglected Starter

If you pulled this out of your fridge what would your reaction be?

This “black” layer is hooch that is showing that my starter is sick and anemic.

Usually I remember my yeast when I haven’t used it for two weeks. It has this layer of hooch on it, but it’s clear. This is the worst that I’ve been a bad yeast mom. BUT I did not kill it.

My initial thought was, “well it’s a good thing I have a freezer yeast back up.” (There will be a future post on this. Now that I have four years invested in this starter, I want to make sure that I have a back up starter that I can fall back on Incase I really blow it and lose my main mother.)

The first thing I did was remove the lid, look for mold and sniff test my starter.

With no mold, I knew I could recover this yeast. And the sniff test confirmed that I hadn’t killed off my yeast. It still had a sour dough tang scent with no additional scent (which would be an indication of a colony of something different from my yeast). My starter smelt weak/anemic. And that’s because it was.

Recovery

The hooch is guaranteed to be where additional growth, competing with my yeast, is living. So first things first, I poured off all the hooch.

As you can see here, there was still some discoloration with the presence of left over hooch.

When I fix neglected starter I always start with a fresh/clean mason jar. I do this because everything about healthy and unhealthy starter is microscopic. I want to minimize the transfer of anything but the yeast I’m rescuing.

Since I don’t want to transfer this tainted hooch, I take a spoon and scoop out this liquid and the top layer of starter.

It’s important to remove the top layer because it was in contact with the pooled hooch. It will be the part of the starter that has the higher counts of any of the foreign colonies (if any is present).

If you want to be extra careful about to continuing contamination, you’ll want to make sure and use a clean spoon with each scoop.

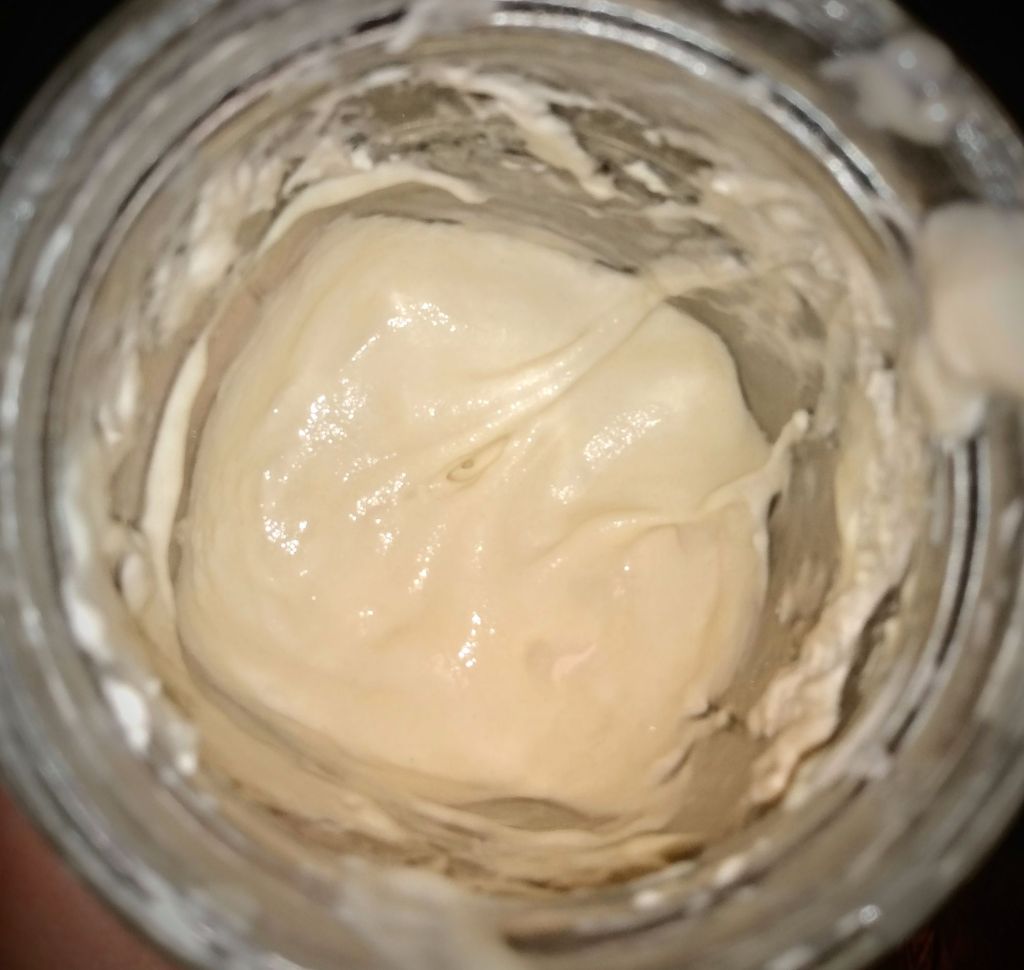

I didn’t take a picture after the first scoop, but this is after a couple of scoops. As you can see in this above picture, there is a distinct color difference between that sickly top layer and this more beige color.

This color difference is a good indication of what needs to be removed and what can be salvaged.

The white layer was watery, pasty, and had every indication of “do not keep me”. The beige layer beneath had a cake batter like texture and looked “healthier” even if this rich color is darker than the color of my normal starter.

Nature is good with communicating information by using layers. So I follow what my yeast tells be and grew confidence that I could absolutely save this starter without having to get the yeast out of my deep freezer and hope I could make that work.

Now that I had the information I needed, I finished scooping out all the left over hooch and the white layer.

With everything removed, I grabbed my clean jar and started scooping out starter from this jar and depositing it in the new jar.

Because I wanted to minimize anything that might be deeper in the jar, I only scooped out starter from the center. I was careful not to get starter from the sides of the jar or from the bottom.

Normally I try to transfer as much starter as I can scrape out of the jar. This is an instance where that was not going to happen. Again, my goal here was to stay away from any potential starter that was exposed to the hooch.

The good news is that even if all you have to transfer is a couple of soup spoons worth of starter, that’s enough to recolonize a starter.

The amount of starter that I estimate I put in the clean jar was maybe 1/4 Cup. (I’m not as confident about guessing how many grams as this is the unit of measurement that I didn’t grow up using. However because I use the metric system for bread making, 50-75 grams is definitely more than enough to restart your starter for the ability of having enough yeast in your colony for bread making in a day or two.) Even the tiniest amount of transfer starter is enough to get you going again. Just know that until you build your colony up, your raise time is going to be slow and weak. You do have yeast, it will just take time to build your numbers back up.

Next I added salt into the yeast that I just transferred. As you can see above, I used about a teaspoon worth.

In Meet Frankenstein I talked about the gluten free starter I made and how I had to bring that one back to health. That starter had a different issue that I was resuscitating it back from, but the treatment is still the same… salt. The reason why salt is your first aid for wild yeast starter is because the salt creates an environment that decreases the growth of everything that is competing with your yeast colony. And at the same time salt does not affect the growth of your yeast.

At a previous time I had used 2-3 teaspoons of salt for a starter that was healthier than this one. My starter bounced back quickly. It made my first batch of bread excessively salty. (So make sure that your first bread after a treatment cut back on the salt.) Even still there was no negative effect of the salt on my starter. So don’t feel like you can be too heavy handed. I still wouldn’t put in an absence amount. First you just don’t need it. Second, if you treat all your kitchen resources as valuable (whether they become scarce or just because it frees up a few cents to put elsewhere in your budget) you just use what you need to use to get the job down.

Now can you use too little???

I haven’t yet experimented on how little you can get by to bring your yeast back into health. Here’s what I would look for though if I suddenly ran out of salt and only had a pinch to put in. If my yeast became discolored, hooch formed again, if the hooch is not clear, there is an off scent to your starter… add more salt.

Once the salt is in the jar, give the starter a good stir. This gets the salt where you want it working. If you feed your starter first, the salt is going to be diluted.

When I first started on my journey with a starter I noticed that I don’t stir as thoroughly as I thought I did. Originally I ended up with starter kept on the bottom of my jar and hydrated flour on the top of my jar. That’s another story for another day. But that’s how I came to understand that just because you have a consistency that you think is right, it doesn’t mean that you thoroughly stir and blended everything.

So that is why when I treat with salt, I treat my starter first. Then I feed it.

After the salt treatment I start my feeding process. Water first!

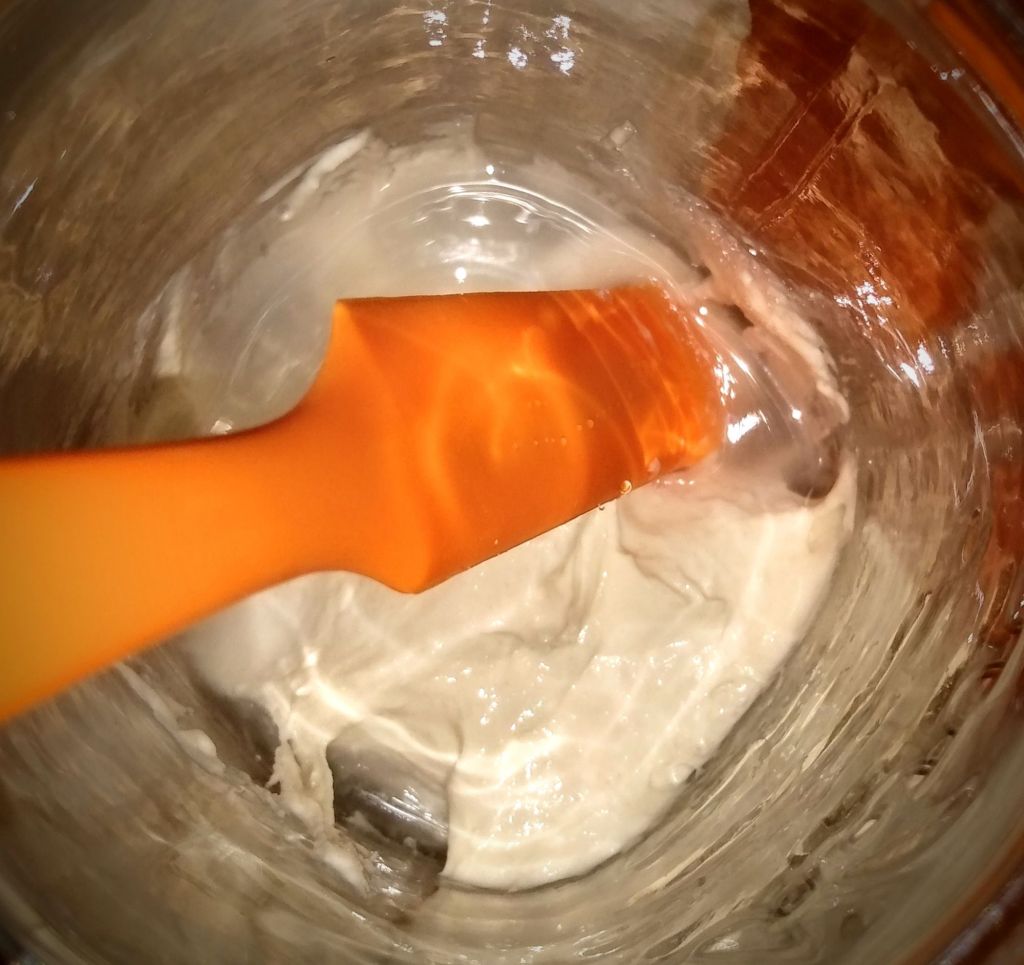

I changed the way that I feed my starter. I now start my feeding with water because this dilutes yeast and ensures that it’s fully incorporated throughout the fed starter. There is no second guessing if I’ve stirred enough to completely incorporate the yeast into the flour. The colony is spread out entirely through all of the water. So when I stir in the flour, everything that is wet has yeast.

As you can see here, there is no doubt that my starter and water are fully incorporated. And it just takes a couple stirs, less than my eggs take when I scramble them.

Bread Recipe That Hasn’t Failed Me is the post where I share my bread recipe that I always use. And since I know how much starter that I need to make two loaves of bread, I know exactly how much to feed my starter. I use 300g so when I pour the water, I aim for 150g. And that means that I also start off with 150g of flour. Once I have that measurement in my mason jar I stir it and check my consistency. Depending on the humidity levels in my house, I tend to always add about 15-20g more flour. This gives me a thick brownie batter consistency. When I keep my starter with this thicker consistency I never have hooch (unless I neglect it for longer than 2 weeks–and that error is on me).

And as you can see with the picture on above right, I stir my flour in just enough to incorporate it into the yeast water. The flour is the food for the yeast, so as long as the yeast water is connected and mixed in with the flour the yeast will find its food and go to town.

As a little side note, I make bread one to two times a week. By the time I get to my yeast, these flour lumps are no longer there. The flour continues to hydrate during the rise time.

I keep my yeast in a quart jar. After a feeding, my starter fills around half the jar. I don’t keep a rubber band around my jar because I know that my yeast is ready when it reaches the top of my jar.

As you see here, my yeast still needed to rise a bit more. But the time in my day was running out and needed to make my bread dough, so I cut my time short.

TIP: My mom hack for making bread with no time to do it during the day is that I make my dough after dinner (right before I start to relax for the night), put it in my bread molds, and let it proof in my oven over night. When I wake up in the morning I turn on my oven (without touching my bread and deflating my rise) and let it cook. By the time lunch comes around, my bread is cooled and ready to slice.

Normally, when I leave my starter out on my counter to double, it takes anywhere from 1-3 hours depending on how cool my house is. When I took the above picture (directly before making a batch of bread) 9 hours have passed and it really could have used another hour our two.

My starter took this long to grow even that much was because the yeast was weak from being neglected. This didn’t concern me. I would have been concerned if there was no rise at all. But obviously I have yeast in there and they were doing their job.

I took a picture of the top of the jar, with the only thing I did was remove the lid, so you could see that there was no hooch. There was no discoloration. This picture tells you nothing as far as smell. But it was predominantly the sour yeasty smell. BUT there was also a flour smell to it. You will notice this flour note when you first feed your starter because you have unprocessed flour in the jar. The fact that the yeast had grown and ate the flour, the smell of flour tells me that the yeast is still weak and the flour hasn’t been all eaten up. This doesn’t raise any red flags. It just tells me that I should expect my proofing to take longer than if my yeast is healthy and happy.

What to Expect After Treating Your Yeast

As I mentioned above, the first thing you should expect is that your yeast is going to take longer to double. I mentioned that my yeast, in my home, normally takes 1-3 hours to double. If I feed my yeast and immediately store it in my fridge, it will double in about 3 days.

Because of how long it took my yeast to double after this treatment, had I put it in my fridge after feeding, it probably would have taken a 5-7 days to double. My guess is about 5 days because that’s how long it took when I treated my starter before after 2 weeks of neglect.

The point to this is that you should expect your yeast to double over a much longer time. There’s nothing wrong with your yeast. It just takes it a hot minute to start eating and doubling its colony population.

Once your yeast has come to a usable stage, the next thing that you should expect is that the flavor is going to be off. If your starter has a sour smell and flavor to it, this first doubling time is going to make it milder

almost no sour flavor

The mild flavor isn’t going to be an issue. What will be an issue is the fact that you will be able to taste the salt that you used to treat your starter.

If you choose to use your starter as usual, and keep true to your recipe, you will most definitely taste that your bread is more salty.

The time that I aggressively salted my starter and used my bread recipe as usual, the bread was inedible for sandwiches. I had to use the bread differently–namely as grilled sandwiches and as bread cubes or crumbs for a recipe.

INSTEAD go ahead and alter your bread recipe up front.

With the bread recipe that I use, I now immediately halve my salt portion of the recipe. So instead of using 22g of salt I use 11g. By doing this there was no change in the saltiness of the bread. It tasted normal.

I know that most people don’t taste this difference that I do, but using treated starter in a bread recipe (even when you cut back on the salt portion of your recipe) tastes exactly like the dry active yeast that you buy in the store. I’ve always had this problem with the flavor of bread from conventional dry active yeast. I always had to add herbs to get a bread that tasted good (garlic, onion, oregano, rosemary, etc.).

In the same manner, with the bread that I made with this recovery from a month long neglect I had to add ground herbs. So in addition to the dry ingredients that are in the bread recipe, I added:

(Herbs were from my garden this year and dehydrated for winter use)

- 1 tsp ground oregano

- 1 tsp ground rosemary

And for the salt portion of the recipe I used garlic salt instead of standard salt.

I mention this because I want to inspire you to use other ingredients with your bread making, especially when you’re compensating for weak/recovering starter. These herbs do nothing to change the function of your bread rising. But it absolutely makes your bread more enjoyable.

Do you have any questions about the starter that you’ve been keeping? Comment below.

Links to previous bread and yeast related posts:

If you have limited resources or want to know how to make a no discard starter, this post will get you started.

Bread Recipe that Hasn’t Failed Me

I share with you my favorite bread recipe as well as how to make pull apart rolls.

If you’re looking for how to make a gluten free starter, here is how I made a starter from potatoes. I also share with you how I overcame my first major obstacle with creating a starter.

Leave a comment